Options traders love talking about “max pain” — especially on expiration day.

Some swear it’s a secret weapon, others say it’s noise. What most traders miss, though, is how differently max pain behaves on SPX vs SPY.

The settlement mechanics, hedging flows, and who actually trades these products all shape how each one moves into expiration.

Here, I want to zoom in on the practical question I get from subscribers all the time:

“Should I care more about SPX max pain or SPY max pain when I’m trading spreads into expiry?”

I’ve been trading index options for more than two decades, and today most of my automated systems are built around SPX. That’s not because SPY is “bad” — it’s because the way max pain plays out on SPX is cleaner, more institutional, and easier to use inside a rules-based strategy. SPY, on the other hand, behaves more like a stock: noisy, reactive, and heavily influenced by retail and ETF flows.

In this article, I’ll walk you through:

- What max pain actually means in plain English

- The key structural differences between SPX and SPY

- Why those differences change how reliable max pain levels are

By the end of these sections, you’ll understand why I give more weight to SPX max pain for

expiration-driven strategies and where SPY still earns its place on my screen.

Before we go deeper, if you need a quick refresher on how max pain works in general, you may want to read my Max Pain Strategy Guide or my beginner-friendly explanation of what max pain is and how I use it in SPX and SPY options. This article builds directly on those foundations.

What Is Max Pain (In Plain English)?

Let’s strip away the jargon. Max pain is simply the price level where the

largest combined amount of call and put open interest would expire worthless.

In other words, it’s the price where option buyers feel the most “pain” and option sellers

(often market makers) keep the most premium.

The theory behind it is straightforward:

- Market makers are usually net sellers of options.

- They hedge their risk using the underlying (SPX index or SPY ETF).

- As expiration approaches, their hedging activity can push price toward levels

where they lose the least — often near max pain.

When enough open interest is stacked around a specific cluster of strikes and hedging flows

are strong, the underlying can start to “gravitate” toward that level. This is what traders

refer to as options expiry pinning.

Here’s a simplified example to make it concrete:

- Imagine SPX is trading around 4,580.

- The biggest combined open interest in calls and puts sits at the 4,600 strike.

- That 4,600 level is calculated as the max pain price for the day.

As we move into expiration, dealers hedging large positions around 4,600 might be buying on dips

and selling on rallies. That activity can naturally slow the market’s movement away from 4,600

and, in quieter conditions, gravity often wins: SPX drifts and closes near that level.

The important thing to remember:

max pain is a guide, not a guarantee.

News events, macro flows, or aggressive directional traders can overpower it at any time.

But in calm markets, especially in index products, you see this pinning effect often enough

that it’s worth paying attention to.

Quick Overview: The Core Differences Between SPX and SPY

Before we can compare how reliable max pain is on SPX vs SPY, we need a clear picture of

what each product actually is and how it settles. On the surface they both track the

S&P 500, but structurally they are very different instruments.

SPX – Cash-Settled Index

- Underlying: The S&P 500 index (no actual shares involved).

- Settlement: Cash-settled; you never receive or deliver stock.

- Participants: Dominated by institutions, funds, and hedgers.

- Contract Size: Larger notional exposure per contract.

- Expiration Mechanics: Mix of AM-settled monthly options

and PM-settled weeklies.

Because SPX is cash-settled, market makers and institutions are focused on

managing their price risk (delta, gamma) rather than worrying about ending up long

or short tons of shares after expiry. That creates cleaner, more orderly hedging flows —

which is exactly the environment where max pain and pinning behavior tend to show up clearly.

SPY – Share-Settled ETF

- Underlying: The SPDR S&P 500 ETF (actual shares trade).

- Settlement: Share-settled; assignment means shares delivered or received.

- Participants: Heavy retail activity plus ETF arbitrage and intraday trading.

- Contract Size: Smaller notional exposure per contract compared to SPX.

- Expiration Mechanics: All options are PM-settled at the closing price.

If you’re trading defined-risk spreads, these settlement mechanics matter a lot. SPX’s cash settlement is a big reason max pain levels behave more consistently, which I break down further in my 100-expiration max pain accuracy study.

In SPY, market makers must think about inventory risk: how many shares they’re

carrying, how assignment will affect their book, and how ETF creation/redemption flows might

impact price. Add on top of that the constant noise from retail traders, intraday scalpers,

and algorithmic ETF flows, and you get a product that is much more jumpy and reactive.

These structural differences are the reason why, in my own trading,

SPX max pain is usually a meaningful reference level for expiration,

while SPY max pain is more of a soft reference zone. In the next sections of the article

(beyond this excerpt), I break down how that plays out in real expirations, which instrument

pins more cleanly, and how I use that in my defined-risk spread strategies.

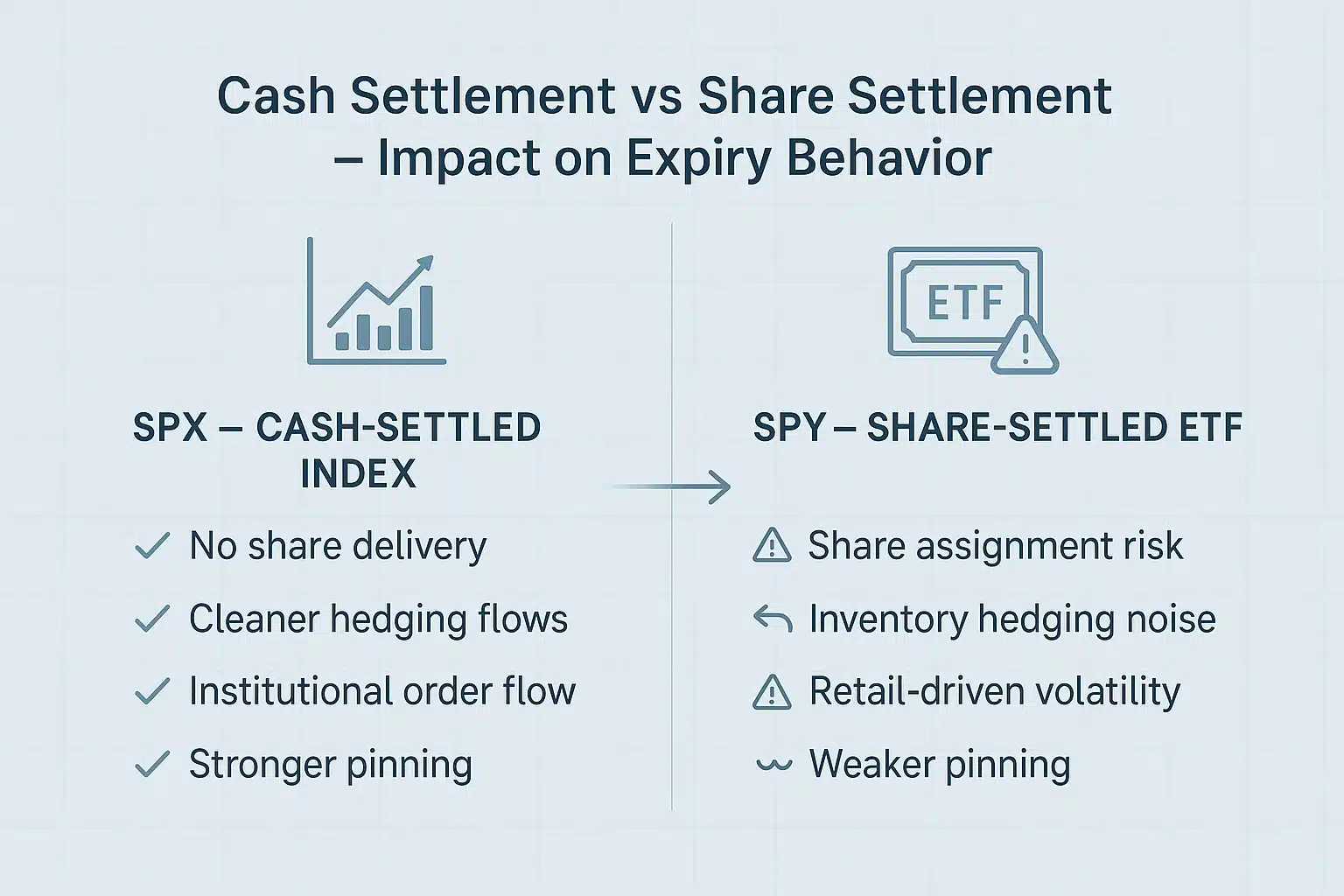

Cash Settlement vs Share Settlement — Impact on Expiry Behavior

Why Max Pain Behaves Differently on SPX

This is where the real divergence between SPX and SPY begins. Even though both track the

S&P 500, their expiration mechanics produce completely different hedging flows.

After watching thousands of expirations over the years — both manually and through my automated

systems — I can tell you that SPX behaves far more “orderly” into expiry.

1. Cash Settlement Creates Clean Expirations

SPX options settle in cash. That single feature removes the biggest source of expiration chaos:

share delivery.

Market makers don’t have to worry about being assigned thousands of shares on a Friday

afternoon — they simply square off cash differences.

This leads to:

- far less assignment-driven volatility,

- no need to unwind large share positions late in the day,

- cleaner, more predictable hedging flows,

- and stronger alignment between options open interest and index behavior.

In practice, this is one reason SPX often “glides” toward heavy open-interest strikes when

volatility is low. Market makers can hedge purely based on price risk, not inventory risk.

This cleaner expiration flow is also why SPX is the backbone of most of my automated credit spread systems. If you want the full ruleset, I walk through it step-by-step in my guide on using max pain with credit spreads and iron condors.

2. Institutional Order Flow Dominates

SPX is an institutional product. Pension funds, insurance companies, volatility funds,

structured-product desks — they all use SPX options as a core hedging tool. Their flows are:

- large,

- methodical,

- and typically predictable.

When these players are hedging near a specific strike cluster — often round numbers like 4500,

4600, or 4700 — the index can stabilize around those levels because dealers are adjusting

deltas in controlled, systematic ways.

This institutional footprint is why, in calmer markets, you’ll see SPX pin so cleanly

that it almost looks engineered. It isn’t — it’s just the natural effect of large hedgers

adjusting exposure into expiration.

3. AM Settlement on Monthly Expirations

SPX monthly options settle based on the opening rotation on Friday morning —

not the closing print. That changes the entire rhythm of expiration:

- hedging pressure peaks into Thursday’s close,

- dealers rebalance aggressively late Thursday afternoon,

- and the actual settlement price is determined by Friday’s opening auction.

This is one reason you sometimes see SPX behave more predictably the day before

expiration than on expiration itself.

This Thursday-effect shows up repeatedly in historical data as well. My 100-expiration research found that Wednesday and Thursday flows consistently create the cleanest pinning behavior, which is why many traders lean on mid-week automated SPX spreads.

Most dealers want to be delta-neutral heading into the

opening print, so Thursday’s price action often reflects max pain dynamics more cleanly

than Friday’s first 15 minutes.

Why Max Pain Behaves Differently on SPY

SPY may track the same index, but it trades nothing like SPX around expiration.

The ETF structure adds layers of noise that distort max pain levels — and I see this play out

consistently across my intraday flow models.

1. Share Settlement Changes Dealer Behavior

SPY options are share-settled, which means assignment results in actual shares

changing hands. Market makers must manage:

- inventory size,

- stock borrow availability,

- ETF creation/redemption baskets,

- and the risk of ending up massively long or short after the bell.

This forces dealers to constantly rebalance share positions, breaking the

smooth delta/gamma hedging relationships you see on SPX. As a result, SPY price action tends

to deviate from max pain levels more often.

2. Heavy Retail Flow Adds Noise

SPY is one of the most actively traded ETFs in the world — and much of that flow comes from

retail traders, short-term scalpers, and intraday algorithmic strategies. When retail traders

chase moves or react to headlines, their order flow can easily overpower the subtle push

toward max pain.

That’s why it’s common to see SPY trading several dollars away from its max pain level

throughout the day, even when open interest suggests pinning should occur.

3. PM Settlement Increases Late-Day Volatility

Unlike SPX, all SPY options settle at the closing price. The final minutes

of the session are often dominated by:

- ETF rebalancing,

- closing auction imbalances,

- end-of-day hedging and unwinding,

- and institutional equity flows unrelated to options.

Even if SPY drifts toward max pain midday, a late-day surge in ETF-related order flow

can completely overpower the pinning effect. This is exactly why SPY max pain should be viewed

as a reference zone — not a precise magnet — for intraday traders.

If you want to see these SPY-specific behaviors in isolation, I break them down with real examples in my SPY Max Pain guide. SPY can still offer useful context, but its max pain levels must be treated as soft zones rather than precise magnets.

Pinning Strength Comparison: SPX vs SPY

Based on every expiration dataset I’ve analyzed over the years — and the live behavior I see

inside my automated credit-spread systems — the conclusion is simple:

SPX pins more cleanly and more consistently than SPY.

Here’s why:

- SPX is cash-settled → no share delivery distortions

- Dealer hedging is cleaner and more predictable

- Institutional flows dominate the order book

- Open interest clusters often sit on round numbers (strong psychological magnets)

- AM-settled monthly expirations reduce closing-auction volatility

SPY, by comparison, behaves like any heavily traded stock: noisy, reactive, and influenced by

ETF mechanics. Max pain can still matter, but the “gravitational pull” is far weaker.

These differences also line up with the raw expiration data from my 100-SPX-expiration analysis, where SPX pinned within ±1% almost half the time, while SPY lagged far behind.

Quick Example: SPX Pins, SPY Overshoots

SPX example:

- Max pain: 4600

- Afternoon price: 4614

- Dealers hedge short-call exposure → selling pushes price lower

- SPX closes: 4603.7

Classic, clean SPX pin.

SPY example:

- Max pain: 460

- Afternoon price: 463.50

- ETF flows + retail momentum push price around

- SPY closes: 462.8

Max pain visible, but nowhere near a precise pin.

This difference is exactly why expiration-driven strategies, including defined-risk

credit spreads, tend to use SPX as the primary reference point — and why SPY is better

for intraday context, not precise expiration targeting.

How Automated Trading Handles SPX vs SPY Max Pain

When you run automated systems — especially ones built around weekly credit spreads like mine —

you quickly see how differently SPX and SPY respond to max pain dynamics.

The most important distinction is this:

SPX max pain behaves like a structural force, while SPY max pain behaves like a sentiment zone.

My automated engines treat the two products very differently because their market microstructure

is nothing alike. SPX flows are slower, heavier, and institution-driven.

This is also why almost all of my systematic credit-spread engines use SPX as the base product. If you want to replicate the exact filters I use (volatility regime, distance from max pain, and OI clusters), you can see the full flow in my Automated Options Trading Guide.

SPY flows are reactive

and often dominated by retail and ETF arbitrage.

How Automated Systems Interpret SPX

SPX is ideal for systematic trading because the flows driving it are consistent.

Dealer hedging is orderly, and open interest tends to cluster tightly around round numbers —

creating natural magnets during calm market conditions.

For automation, this leads to clear advantages:

- Cleaner hedging flows → easier modeling of expiry drift

- More predictable gamma behavior → tighter risk modeling

- Institutional order flow → less random noise

- Better alignment with max pain → stronger expiration pinning

This is why most of my defined-risk weekly strategies — including the credit spreads sent

through Weekly Trend and Weekly Premium — are based on SPX. It’s simply more compatible

with rule-based execution.

How Automated Systems Interpret SPY

SPY is too noisy to treat max pain as a primary driver. Retail orders, ETF creation/redemption,

and intraday flows distort the clean mechanics you see in SPX.

Automated systems must adjust for:

- Intraday volume spikes that overpower hedging flows

- Retail-driven volatility around headlines

- Share-delivery hedging that breaks pinning behavior

- PM-settlement volatility near the closing auction

Because of this, SPY max pain is used in my systems as a secondary confirmation tool,

not as a predictive anchor. It helps indicate zones of interest — not exact expiration magnets.

When Traders Should Use SPX Max Pain

Not all max pain signals are created equal. In my experience — both manual and automated —

SPX max pain is most useful when you’re trading defined-risk spread strategies

into expiration, especially in calmer markets.

You should lean on SPX max pain when:

- You trade SPX credit spreads (bull put spreads, bear call spreads, iron condors)

- You want reliable institutional signals on expiry days

- Volatility is low and market conditions are stable

- You’re looking for a clean, predictable expiration drift

- You want to model dealer hedging flows directly

If you trade defined-risk SPX spreads, this is where max pain becomes a genuine advantage. You can see how I apply these exact conditions to real spreads in my walkthrough on using max pain with credit spreads and iron condors.

These are the exact conditions where max pain can act like a gravitational pull — not always,

but often enough to matter. If you’ve ever watched SPX chop around a round number for hours

on a Thursday afternoon, you’ve seen this in action.

This is also why most institutional traders and structured-product desks rely on

SPX for weekly hedging. The product behaves consistently, and max pain interacts with hedging

flows in a way that’s measurable and repeatable.

When Traders Should Use SPY Max Pain

SPY has its place — it’s just not the same place as SPX. SPY max pain is more useful for

intraday context, retail-flow insight, and identifying broad pressure zones

rather than exact pinning targets.

SPY max pain is helpful when:

- You trade SPY directly (shares or options)

- You want to identify short-term support/resistance levels

- You track retail-driven momentum or headline reactions

- You’re scalping or day trading short-term moves

- You need a “zone of interest,” not a precise expiration target

SPY is a hyper-liquid trading vehicle. It behaves more like an equity than an index, which

means max pain gets diluted by retail traders, ETF flows, and end-of-day auction imbalances.

It’s still useful — but as a broad guide, not as a precise magnet like SPX.

For this reason, in my systems SPY serves as a secondary signal, especially

when SPX and SPY max pain cluster around the same levels. When both instruments show alignment,

the probability of the market respecting those zones increases.

For most traders, SPY max pain is best used as a secondary filter — a way to sense retail-driven magnet zones rather than as a precise expiry target. You can see detailed SPY expiration examples in my SPY Max Pain guide.

Summary Table: SPX vs SPY Max Pain

Users love quick comparisons — and so does Google. A simple summary table like this helps both readers and search engines understand the core differences at a glance.

| Feature | SPX | SPY |

|---|---|---|

| Settlement | Cash | Shares |

| Who Trades It | Institutions | Retail + ETFs |

| Pinning Strength | Strong | Weak–Medium |

| Best Use Case | Credit spreads | Intraday context |

| Expiration Drift | Predictable | Noisy |

Final Verdict: SPX vs SPY Max Pain

After watching thousands of expirations over the years — and building automated strategies around both products — the conclusion is clear:

SPX max pain is more reliable, more consistent, and far more actionable than SPY max pain.

SPX’s cash settlement, institutional participation, round-number clustering, and predictable hedging flows all work together to create cleaner expiration behavior.

When volatility is low, SPX often behaves as though it’s “magnetized” toward heavy open-interest levels.

SPY, by contrast, is influenced by ETF mechanics, retail flows, and the chaotic nature of PM settlement.

Max pain still matters for SPY — but mostly as a zone of interest, not a precise expiration magnet.

It’s excellent for intraday context, but not for pinpointing where the market is likely to settle.

If max pain is part of your trading playbook — especially for defined-risk weekly credit spreads — then

SPX should be your primary guide.

That’s exactly why my automated systems prioritize SPX signals: the behavior is more consistent, the hedging flows are easier to model, and the pinning effect shows up more often.

If you want to see how I apply SPX max pain in live weekly trading — with fully automated SPX iron condors and credit spreads — my Weekly Premium service sends the exact trades I take each week.

It’s designed for traders who want defined-risk, rules-based SPX strategies without needing to monitor the market all day.

FAQs

1. Is SPX max pain more accurate than SPY max pain?

Yes. SPX tends to pin more cleanly due to cash settlement, lower noise, and stronger institutional

hedging flows. SPY behaves more like a stock with frequent intraday volatility and ETF-driven moves.

2. Can SPY max pain still be useful?

Absolutely — just not for precision. SPY max pain is great for identifying zones of interest,

retail sentiment, and short-term support/resistance. But it’s rarely a precise expiration magnet.

3. Does max pain always influence price movement?

No. Max pain is a guide, not a rule. Strong news, macro events, or volatility spikes can easily

overpower hedging flows. Max pain works best in quiet or moderately calm markets.

4. Is max pain a good standalone trading strategy?

Not by itself. Max pain becomes valuable when combined with other factors like volatility conditions,

dealer gamma levels, and liquidity flows. It’s a helpful reference tool — not a trading system.

5. Should I use max pain for credit spreads?

Yes — especially on SPX. When open interest, hedging flows, and volatility align, max pain levels can help you structure safer, more favorable credit spreads. This is a core component of how I build the automated SPX strategies inside Weekly Trend and Weekly Premium.